Saving Chimps

story by Charlotte Zombro, photo by Tyler Diltz, design by Vu Huyn

Not too far from Ellensburg, about 30 minutes down the road, sits something you’d never expect. Just outside of Cle Elum sits a vast acreage of land that is home to over a dozen chimpanzees, and maybe even a few of your classmates.

No, your peers are not chimpanzees, but they are primates and they might be student volunteers at Chimpanzee Sanctuary Northwest (CSNW), where many students both inside and out of CWU’s Primate Behavior and Ecology program choose to intern.

CSNW is, very simply, a safe space for captive chimpanzees to live out the remainder of their lives. “It's a home to chimpanzees that have previously been treated by humans in ways that we don't agree with,” says volunteer manager Anna Wallace, “and so we give them the best life we can.”

From a Tragic Past…

For the 16 chimpanzees residing at CSNW, every aspect of life at the sanctuary was an improvement. From a life of constant poking and prodding, lonely concrete floors and ceilings, to acres of grass and a whole new community of like-minded chimpanzees, there has been a steep learning curve for many of them.

“Most chimps in the United States have come from biomedical research,” says Dr. Mary Lee Jensvold, senior lecturer at CWU and Associate Director at the Fauna Foundation in Quebec. “There are some that have come from entertainment and some were former pets and some coming from roadside zoos or zoos that are not accredited by the American Zoological Association. But really, if you look at the demographics, most of them are coming from laboratories.”

If hearing “biomedical research” in this context makes you a little queasy, you’re on the right track. Many of our closest living non-human relatives were purposefully infected with diseases such as HIV and hepatitis C in the hopes of gaining medical insight, to varying degrees of ‘success,’ if you can call it that. Jensvold describes the specific kind of testing done, explaining, “They were used in toxicology research, other infectious diseases besides HIV. Originally they were used in the space program, so what happens if their body endures impacts? That is… historically is how they were used.”

Jensvold describes the pain and isolation many of the animals went through in that environment, sharing the story of Sue Ellen, a chimp currently residing at the Fauna Foundation. Jensvold describes how, according to her medical records, Sue Ellen had undergone invasive procedures almost weekly for an entire year.

“They were doing something called a punch liver biopsy, where it's like cord drilling into your liver,” says Jensvold. “She would be put under anesthesia, which is not a pleasant experience, and then they would use a large gauge needle to basically just punch into her liver and pull out tissue to see what was going on in her liver.”

If the pain of frequent biopsies wasn’t enough, the chimpanzees involved in medical testing were often housed in solitude, maybe catching a passing glimpse at another chimp once or twice a day. “It can be really hard to integrate chimps that come from those backgrounds,” explains JB Mulcahey, Co-Director of CSNW, “because chimps learn things through their cultures like we do, so when you live alone, there's no culture to learn from and those chimps have a really hard time adapting.”

A group of ragtag rescued primate patients was exactly what got CSNW started 17 years ago, and they have been adjusting to meet the ever changing needs of their residents ever since.

“We started in 2008 with the rescue of a group of chimps from a biomedical research facility in Pennsylvania, and since then have taken in 11 more chimps from various failed facilities and roadside zoos,” says Mulcahey.

With 16 chimpanzees, three cows and plenty of employees and volunteers, there is a lot of personality to be found at CSNW. Each chimpanzee has a story and each caretaker is eager and ready to share that story with anyone who is willing to listen. One chimpanzee with a particularly interesting story and unique set of quirks is Foxie, a rather introverted chimp with a love for dolls.

To understand Foxie’s story, you first have to understand the conditions she experienced before arriving at CSNW. “When chimpanzees come out of these laboratories, in many cases they are institutionalized,” explains Mulcahey. “So like human prisoners that have been incarcerated for decades, they kind of adjust to that prison setting and have trouble adapting on the outside.”

“Chimps, similarly, they kind of get used to the concrete and the steel and things like that, and then when they're brought to a sanctuary, they're nervous about things like stepping on grass, sky overhead without bars.”

“Foxie was an incredibly institutionalized chimp, and when we rescued her, we would give the chimps all these fleece blankets at night to make these nests, but she would push them all out of the way just to make a bare spot on the concrete floor. That's all she wanted was just to be by herself on the concrete floor,” Mulcahey continues.

“Then a couple months later, we put out just a random assortment of toys for the chimps and she picked up a doll, and it's been about 17 years now that she has had a doll with her at all times. Sometimes she has them in both hands, both feet, one on the back.”

…To a Carefree Future

PULSE got the honor of visiting CSNW and seeing Foxie and her dolls in the flesh, and it is exactly as Mulcahey describes. Foxie can be seen casually milling about the grassy hill, dragging a small doll behind her or slinging it right up onto her back, just behind her head to keep it in place as she goes about her day.

Foxie isn’t the only chimp with a big personality at CSNW. Our reporters got a warm welcome from quite a few of the sanctuary’s residents. April Binder, the director of CWU’s Primate Behavior and Ecology program, has many things on her mind when visiting CSNW, her footwear not least of all. “Whenever I get to go to the sanctuary, I know that Jamie loves shoes. So I always put a thought process into what shoes I might wear for the visit so that I can see if she's interested, if they get the Jamie approval or not,” she says.

That's right. While you do need some strong footwear to navigate the rugged terrain of the hillside sanctuary, you also need to take style into consideration, lest you end up on chimpanzee Jamie’s worst dressed list. Jamie herself stared down one of our reporters expectantly, until Mulcahey revealed what she wanted: “She wants to see your shoes.”

After a brief fashion show and a resounding “meh” from Jamie, we moved along.

The newest arrival to CSNW is a young chimp named George. “We had known about George for over a decade,” says Mulcahey. “He was held at a roadside zoo in southern Oregon.”

“When he was young he was on a television show in Germany, so he was in the entertainment industry, taken from his mom early on,” he continues. “When he was done being used as an entertainer, he was sold to this roadside zoo and he lived with one older female chimpanzee there, which is not a large enough group to satisfy a chimp's social needs. When Daphne, that other chimp, died, he lived alone for a year and a half.”

“Earlier this year we got word that the zoo was going to be raided and that the animals would be confiscated by the government, and they asked if we would be able to take George. So we thought about it for about an hour, and then said, ‘of course we'll find a way to take him.’”

“He has been here since May. He's 21 years old. He is the most charming chimp you'll ever meet. He’s got all of the energy and enthusiasm of a young chimp, so he's loud, he's boisterous, but he's also incredibly gentle and sweet.”

Mulcahey explains the danger of integrating rescued chimpanzees from the very unchimplike environments they were brought up in. He says, “It's a big risk… when one chimp is joining a group. Especially if they don't have social skills, they can get ganged up on and beat up pretty bad, but so far he is navigating all of this much better than we thought he would.”

While 21 year old George is living out his partying years at CSNW, many of the other chimps are entering their golden years excited to finally have some rest and relaxation.

Negra is the oldest chimpanzee at the sanctuary at around 52 years old. She has had her fair share of struggles, some of which may be relatable to many human readers.

“She was actually wild caught. Up until the mid 1970s, it was legal to capture chimpanzees in Africa and then ship them off to various countries; Japan, European countries, Canada, the US specifically, often for research or for entertainment,” says Mulcahey.

“In those cases, you can't just go out into the forest and take a baby chimpanzee, the [chimpanzee’s] community won't let you. So in many cases, the adults, including the mom, are killed to capture the infants and juveniles, so we actually don't know anything about her early history. All we know is that she ended up in biomedical research when she was young and spent the better part of 35 years in cages, about three feet by five feet.”

“She was very impacted by that isolation and those conditions. She came to us very withdrawn. We actually had a study done, a primatologist and a psychologist actually worked together to look at signs of PTSD and depression in chimps using the DSM criteria and limiting it to observable behavior.”

“Negra fit the classification for depression, so she's very withdrawn. She would stay in bed all day, she's very overweight, lethargic; and she's still slow, overweight, does things at her own speed, but she's really come out of her shell. She's a really interesting case.”

At CSNW, there is a shining light for struggling chimps like Negra. Those who enter the sanctuary fearful and downtrodden are able to find a space to roam, to feel the grass beneath their feet, as foreign as that feeling may be.

With a two and half acre enclosure to explore, it takes some time for the chimpanzees to see all that it has to offer, and Negra is no different. “We first built a variation of this enclosure in 2011,” says Mulcahey, “and it wasn't until just a couple years ago that she went to the very top of it. So it took her a decade to either find the courage or just develop an interest in going that far from the building.”

As Mulcahey gears up to take our reporters on the same walk that took Negra a decade to make, he claps his hand by a tunnel leading from the building to the grass enclosure. Suddenly, a male chimp eagerly climbs through the tunnel, leading the way up the hillside. It's Burrito, a chimp with a dark past as a test subject and a bright future as a tour guide as he walks in tandem with Mulcahey and company, patiently waiting as we stop to talk.

There is something very profound in walking in step with an ancient relative. The connection weighs heaviest in the shared glances from chimpanzee to human; their deep brown eyes bring about a sense of kinship, of shared experience. While their backstories are tragic and by all means unrelatable, unfathomable, their personalities and quirks are entirely too familiar.

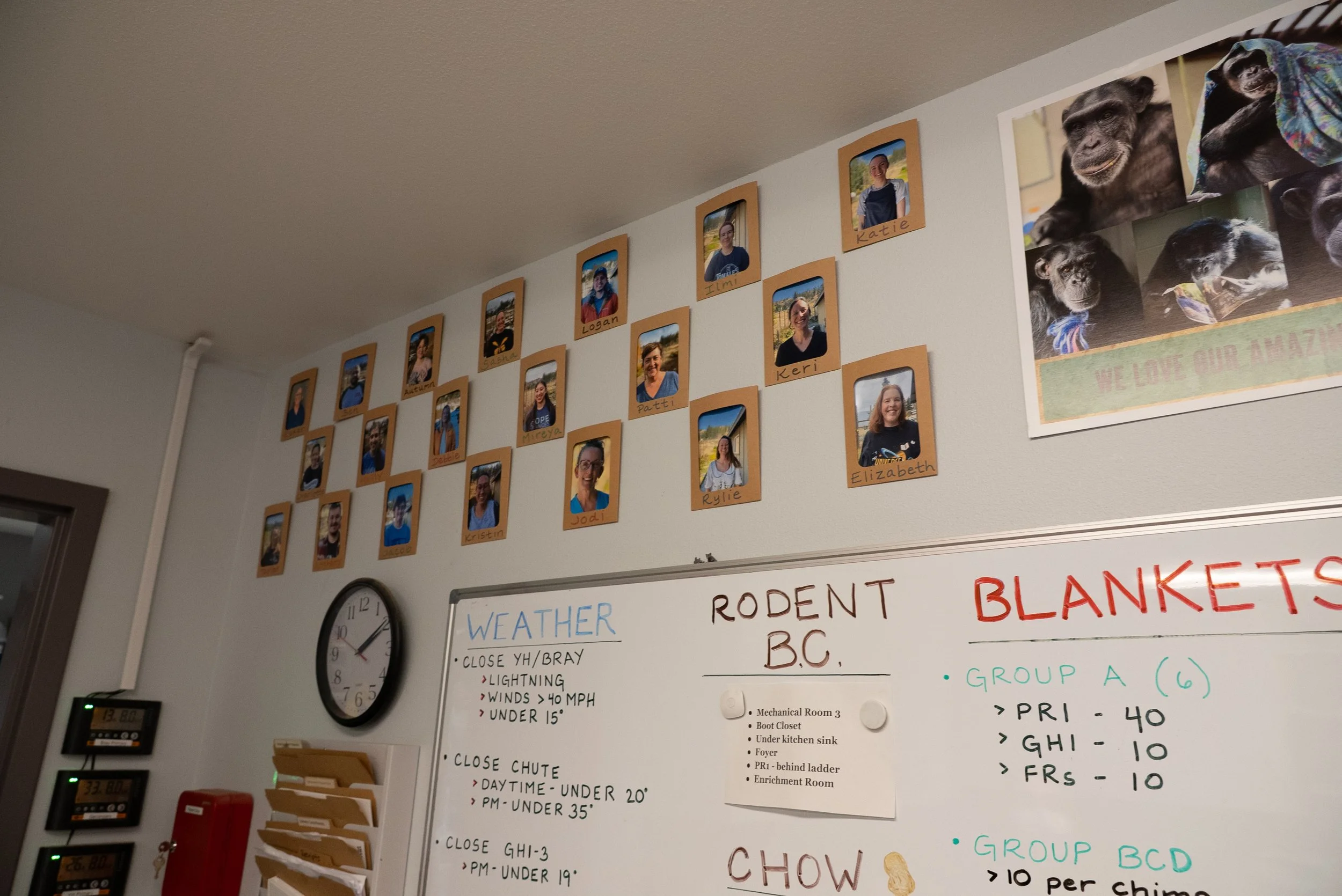

The Humans That Make It Happen

PULSE’s visit was not solely a deep reflection on humanity and our not so distant ancestors. Our reporters also got down and dirty, leaving the sanctuary covered in spit and stink, thanks to a particularly playful chimp.

“Honey B over here, she's kind of mischievous,” says Wallace. “Sometimes she likes to make sure people know that she's in charge, so she'll summon the bottom of her stomach and put that all over you. And while it's uncomfortable to happen, you just know how smart she is. So those kinds of things are always both kind of funny and kind of tragic for those poor caregivers that have to go through it.”

Poor caregivers indeed. Honey B was eager to talk to our reporters and was not about to miss out on her five minutes of fame, launching a mouth full of water onto one and some real, verified, smelly chimp spit onto another. Honey B might as well replace Wallace as volunteer manager seeing as she has a real talent for weeding out those who simply can’t hack it, and we at PULSE are decidedly not cut out for this work.

It takes a special person to do this work at all, in fact. If you have any empathy for those working in childcare, maybe think about extending it to these volunteers who dedicate their time and effort to caring for these animals, reminiscent of big hairy children themselves.

The volunteer duties that Binder describes are not unlike many domestic, housekeeping tasks you might perform on the day to day.

“Really what you're doing is washing fruits and vegetables, chopping fruits and vegetables, getting their food ready for the day, helping to do laundry,” says Binder. “There's a lot of laundry unfolding and organizing, making different enrichments for the animals and getting things ready for them so that they can be used.”

These housekeeping tasks that often fade into the background of our day to day life are the very backbone of CSNW, allowing it to function as it should and give these chimps the life of comfort they have earned after so much hardship at the hands of humans. This makes the job of caretaking volunteers and interns paramount to the success of the sanctuary.

“They help us so much,” says Wallace. “You have a hard day and you're exhausted, but, you know, ‘oh, I've got an intern coming in and they're gonna help me pick up some slack.’ We really need some extra help, just heavy lifting and making sure those little details are taken care of, so it's always super helpful to have them.”

If there was one thing to be gained from the COVID-19 pandemic, CSNW gained a lesson in gratitude.

The sanctuary made use of student volunteers from the very start, just as its predecessor (the Chimpanzee Human Communication Institute) had before them. When Covid hit, everything shut down, and the staff at CSNW found themselves overwhelmed with tasks that had previously been delegated to their devoted volunteers.

“With the pandemic we had to very quickly and abruptly shut down our intern and volunteer program because of the risk of transmitting COVID to the chimps,” Mulcahey explains, “and suddenly it was just the staff.

“We could barely get things clean and get the chimps fed. We didn't have the resources to do all of the extra stuff; putting together food puzzles, enrichment, and the things that really keep them from getting bored day to day.”

Caring for the chimpanzees wasn’t the only thing made more difficult by the pandemic; the lack of community and communication hindered change, progress and the implementation of new practices and ideas.

“We also just realized that suddenly there weren't as many ideas being tossed around, and so we got less creative,” Mulcahey explains. Now, the volunteers are back and more passionate than ever.

Anyone who has spent a winter in Ellensburg understands the changes in needs and routine that come along with the shift in weather, and it is no different for the chimpanzees at CSNW and their caretakers.

“They've got a lot of very similar traits to us, and now as winter comes, everyone likes extra blankets to wrap up in, chimpanzees and us,” Binder explains. Next time you snuggle up in your bed at home, just know there could be a chimpanzee just a few miles away doing the exact same.

This similarity is precisely what draws these caretakers in. CSNW and the world of chimpanzee conservation as a whole is particularly enticing to the most empathetic among us, those who cannot bear to watch a living creature with such intelligence and life struggle to survive.“They're just so smart. It's just such a unique animal to get to know,” says Wallace.

She explains that with the chimps’ displays of personality and their propensity for community, it is hard not to see them as people, just like you and me. “They're amazing people, so you learn to know them as individuals. You are just here to care for these special people that need that extra love.”

“Obviously their similarity to us is what I think draws a lot of people in,” Mulcahey explains. “The first time you see a chimpanzee, even on TV, you just understand a lot of their behavior intuitively, and then there's some things that don't make sense, so you wanna understand why they do them.”

As a whole, CSNW is a place for chimpanzees that need some extra kindness and care, as well as the humans with the capacity to give them that.

“Its so important that they have that piece of caregiving,” explains Jensvold, “I think it teaches compassion and consideration in research, and so for me, it's really wonderful that my students can go up there. I'm glad that we have that resource for them that's close by to Ellensburg now.”

Just a few miles outside of Ellensburg you can find something the likes of which you may never have seen before: a close knit family of dedicated staff caring for an even closer family of animals, and these animals need all the care they can get.