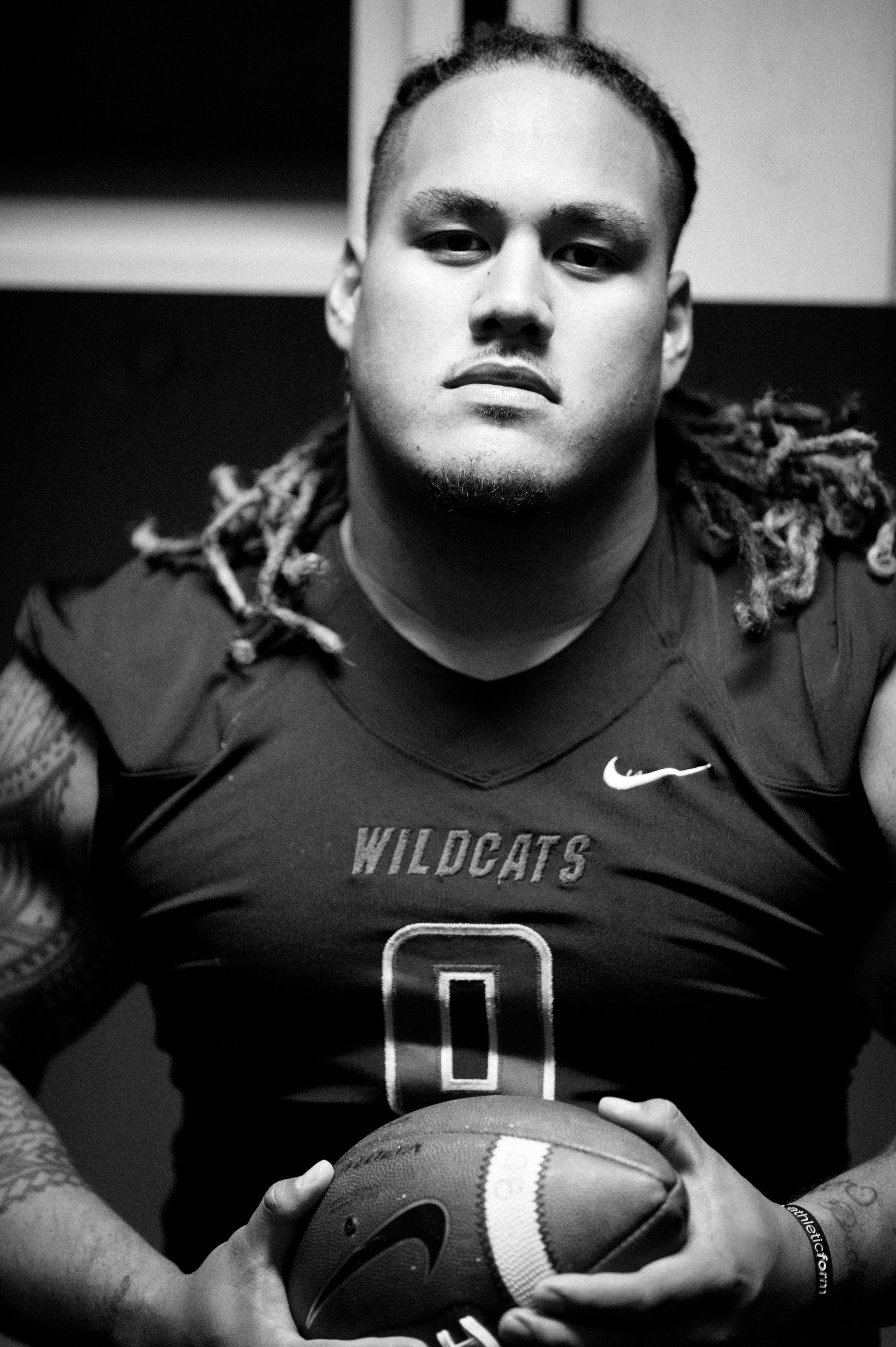

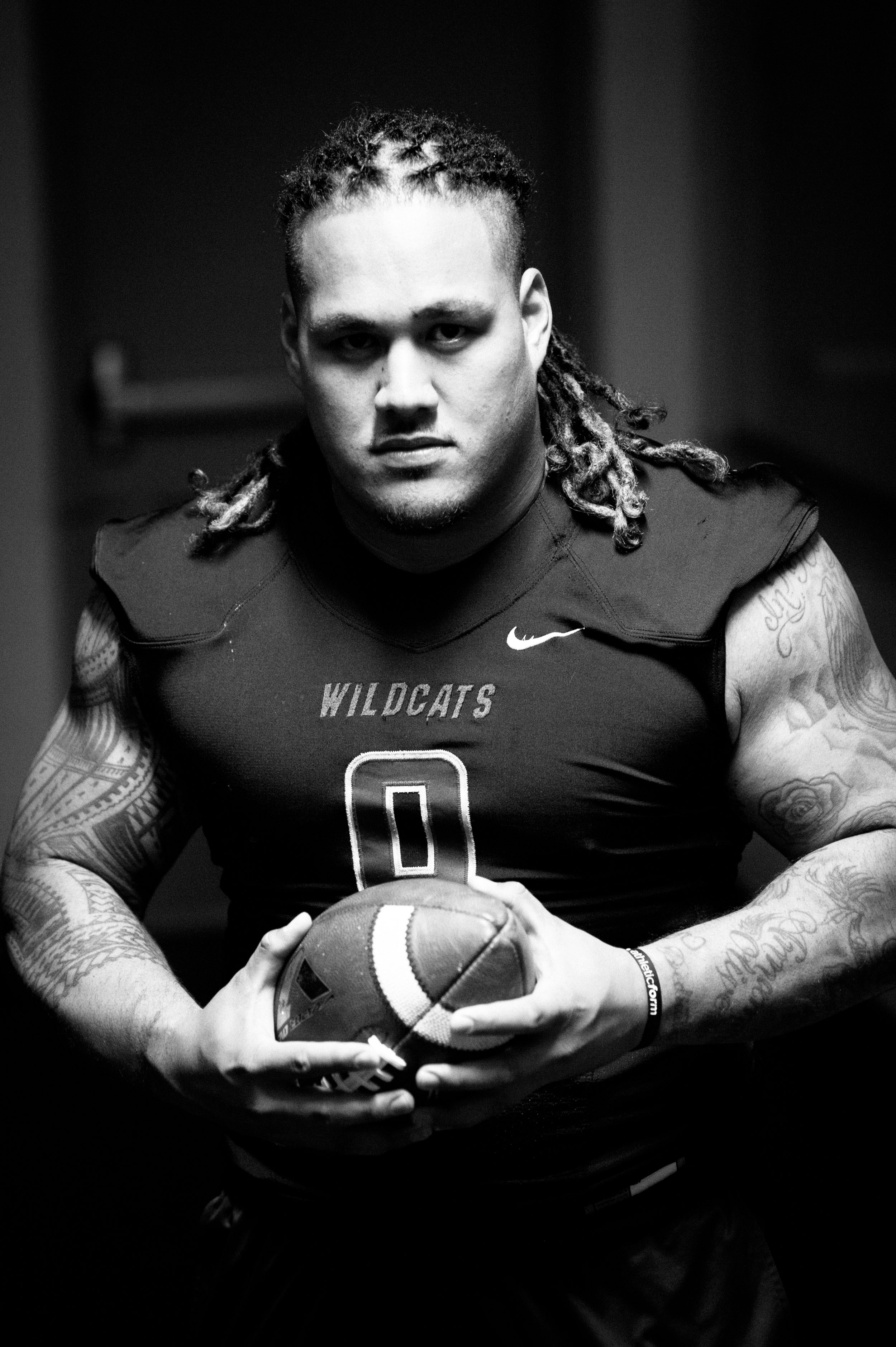

Meet Uso Olivè

Story By: Glendal Correa // Photos By: Xander Fu

3!2!1! ERRRRR!

We’ve all done it. Whether it be in the comfort of our home with a balled up piece of paper and trash bin or while practicing our favorite sport, we’ve all imagined the perfect scenario.

Clock winding down, crowd cheering your name and in the midst of all that pressure you make a game-winning play.

Aspiring athletes spend hours upon hours watching and idolizing their favorite athletes compete while trying to mimic their moves, mannerisms and idiosyncrasies.

Although many of us dream of being these professionals, not many of us have had those moments of athletic greatness outside of our imaginary game-winning bucket in the middle of our living room.

But for Central Washington University defensive tackle, Uso Olivè, that distant and coveted ‘dream’ may soon be a reality.

A standout athlete at Federal Way High School and a household name at the University of Wyoming and CWU, Olivè is part of a select few who are talented enough to see his hopes of being a professional football player come into fruition.

At the end of this month, Olivè is expecting to be picked by a professional football team in the 2017 NFL draft. His football talents have caught the attention of many, but Olivè has always been the one to watch on the gridiron since his days playing pop warner.

After every game a lot of the other kids’ parents would come up to my mom and say, ‘your son’s special,’” says Olivè. “I mean, I didn’t see it. I knew I was making a lot of plays but I was just playing because it was fun.”

At 6’1”, 292 pounds, and a large Polynesian frame, Olivè’s still having ‘fun’ on the football field by putting together an impressive football resume—giving himself a shot at playing in the NFL. He has already visited the Seahawks facility for a workout this month and will probably receive many other professional opportunities.

So, what’s the catch?

The process is long, tiring and much like his life, filled with adversity.

HE DOESN’T KNOW HOW TO GIVE UP”

The odds of becoming a professional athlete, let alone being the best at your respective sport, are so astronomically twisted against you that saying you played a single second in a single game of any professional sport is the coolest thing in the world.

Although it may seem impossible, it’s not as hard when the numbers have always been against you.

For Olivè, hard work is mandatory. Every day consists of training, dieting and class but perhaps his most unrecognized characteristic is how much he has overcome to get to this point.

Teammate and friend Elisha Pa’aga praises Olivè’s passion and attributes it to how Olivé grew up.

“Having Uso as a teammate allows all of us to be comfortable on the field,” Pa’aga says. “His passion is just contagious, I think it comes from his childhood and how he was brought up.”

Olivè grew up in the West Seattle area before going to Federal Way High School where adversity was no stranger.

Olivè’s cousin, Eric Ah Fua, who refers to Olivè as his brother, recalls Olivè having to grow up much faster than most kids his age.

“He had to grow up much earlier than his peers and had to be a man at an early age for his mother,” says Ah Fua. “His father was absent and at the time his mom was sick, so he had to carry a huge load with football, school and taking care of his mom.”

During Olivè’s junior year of high school, his mother and ‘number one supporter’ passed away from health complications. “When my mom passed away, that’s when I really started working at football,” says Olivè. “I started going to camps, winning awards and competing.”

Olivè uses—and continues to use—his mother’s memory as a source of motivation while working towards his goal of graduating from college and making it into the NFL.

“He grew up and didn’t have much, and then lost his mother,” says Ah Fua. “The way his trajectory should’ve went versus where it actually went is amazing and he never made any excuses. He just doesn’t know how to give up.”

Even Olivè recognizes his mother’s death and how it plays a significant role in where he is today.

“That was my turning point and I began to mature because my mom died young and I knew I wanted to finish her life for her,” he says.

THE DRAFT

Olivè’s perseverance brought him to the NFL draft, but that only marks the beginning.

It is a nerve-racking process that could end in an uproar of cheering with family and friends or a silent realization that you weren’t chosen.

All season long during the collegiate football season, NFL teams, scouts and managers are put-ting together a list of their team’s biggest areas of need.

There are seven rounds of drafting in which 32 teams choose one player per round (unless a team has previously traded their pick to another team).

If your name is entered into the draft, you sim-ply wait anxiously with your friends, family, agent or whomever you choose. If you are likely to be one of the top drafted players, you are personally invited to the draft to watch. If not, you watch it televised wherever you want. Athletes who are not drafted may still receive phone calls from coaches whom express interest in their talents. These players are referred to as ‘undrafted free agents,’ and they can practice on a team and earn their spot on a roster.

Olivè hopes his name is called during one of the seven rounds or that his phone rings and a team gives him an opportunity to prove himself, but you don’t just go to the draft. It’s a business process and if you don’t prepare properly and care-fully, this process can take its toll on you.

“IT’S NOT ALL GLITZ AND GLAMOUR”

Past the logistics, cameras and excitement of the NFL, the draft can be burdensome for a student-athlete.

One of the first steps Olivè had to take on the path to the draft (which we often don’t hear about) was hiring an agent. “Picking an agent was harder than deciding what college I wanted to play for,” says Olivè. “It becomes a business. Yeah, [football] is still fun but now there’s a business side to this whole thing.”

At an early age, you’re being asked to choose an individual who will manage your future money, contracts and deals with hardly any agent-choosing experience. This means being very careful about who you choose, knowing the ins and outs of your contract and ultimately making the right choice.

Along with finding people to help manage his career, Olivè struggles with trying to separate people in his life who genuinely care for him, from people who are simply around because he is an NFL prospect.

Before Olivè’s last year at Wyoming, for personal reasons, Olivè decided to come back to the state of Washington to play for CWU. He received backlash for leaving Wyoming from peers and people he cared about, while also dropping from the 32nd defensive tackle in the nation to the 74th.

“It hurt because I felt like people left me because they thought I was done,” Olivè says. “Now, here at Central, I received the newcomer of the year award, 1st team all-conference; the draft is coming up and those people are starting to come back around.”

While it’s a harsh lesson to learn the ups and downs of stardom, Olivè has learned how to handle these situations at an early point in his career.

“There are going to be people who hate you, then love you, then hate you again,” he says. “That’s one thing I don’t like about this process but it’s a part of it and I’ve learned how to deal with it. It’s not all glitz and glamour.”

"THE UNDERDOG”

Making it into the NFL is a big deal because at the end of the day you aren’t supposed to. Mathematically, you are an anomaly and set yourself apart from normal people because you are the best of the best at what you do.

But you don’t become one of the best by sitting around—you grind non-stop, until you feel like you can’t anymore and the only rest you seem to get is in-between sets.

Let’s say you’re not a top draft prospect; then you must train harder than others while harboring a massive chip on your shoulder.

“There’s days where [players] feel like we just don’t want to do this anymore,” says Olivè. “Sometimes it’s too much pressure.”

As a part of training for the draft, Olivè’s agent sent him to Hawaii to train for three months with well-known NFL football trainer Chad Ikei.

“Yes, I went to Hawaii but it was to train and strictly about business,” he says. “I went there weighing in at 330 lbs. with 32 percent body fat and left at 292 lbs. with 17 percent body fat.”

That is a total of 38 lbs. and 15 percent body fat lost in a span of 90 days.

“It was crazy because you had to wake up at five in the morning already thinking about how you were going to attack this day,” he says. “You wake up and your body is aching, you’re tired and you really have to ask yourself if you want to do this.”

After three months of training on the is-land of Oahu, Olivè came back to CWU to help coach, train and graduate.

Don’t be mistaken though, the numbers are still against him and there is still much to prove to take days off.

“Uso loves stories and games about the underdog,” says Elisha Pa’aga. “You’re the underdog when you are low yet still challenge someone with the upper hand and win.”

“IT’S BIGGER THAN ME”

“I just want to walk away from [football] content, knowing I gave this my all because it’s bigger than me,” says Olivè. “The funny thing is, my mom didn’t care about me playing football, she said me graduating would make her happy and I will have done that.”

At the end of the day we can punch in the numbers, measure Olivè’s successes and read about the possibilities, but this has been bigger than the draft.

If draft day arrives and his ticket is pulled, many will be proud. Some may tell stories about how they knew a guy in college who plays in the NFL; others may celebrate his successes as their own.

But with so much anticipation wrapped around the draft and what Olivè may or may not do, we’d be amiss to ignore the most important part of all of this: The journey.

The Numbers

Not to put a damper on aspiring dreams to be the next Jordan, Brady or Phelps, but let’s break it down using the National Football League. According to ncaa.org, there were about 73,660 athletes who participated in collegiate football. Of that large number, 16,369 players were considered “draft eligible,” which means professional teams can choose those players from a seven round lottery draft of talent. Of those 16,369 draft eligible players, 253 players were drafted. That is equal to about 1.5 percent of all college football players. That is why for most athletes the term “dream,” often remain a distant place that we can feel, but maybe never experience and for Olive, getting this close means beating the statistics.